In this case study, we learn about Holly and her son Jack, who has MCADD, and the steps her midwife Ruth took to help during the pregnancy.

Holly is a 30-year-old woman who has two children, Jenny and Jack. In this case study, we will be focusing on Jack, her second child, who was diagnosed with medium chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiency (MCADD) shortly after he was born. She has a partner called Pete, who is the biological father of both children. The community midwife who helped her throughout her pregnancy is called Ruth*.

*For ease of understanding, this case study features a single midwife, however, it is likely that more than one midwife will be involved during a family’s journey.

The booking appointment

After finding out that she was pregnant with her second child, Holly informed her GP who referred her to a local community midwife, Ruth.

Ruth contacted Holly to arrange the booking appointment, which she explained takes around an hour and provides the chance to take a medical and family history to allow the correct pregnancy pathway to be taken.

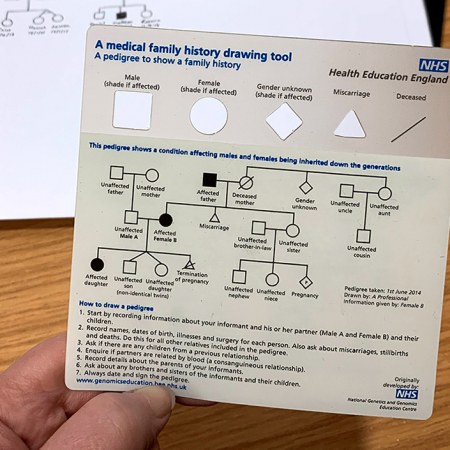

During the appointment, Ruth asked Holly a number of questions, including whether there is a known family history of any medical conditions, or if she or any primary relatives has ever had any genetic counselling.

Holly said that she and her father have asthma but there are no other conditions that she knows about that run in the family. She also said that she wasn’t aware of any family members who had had genetic counselling.

Ruth, knowing how important family history could be for adapting care, asked Holly to let her or any healthcare professional know if she thought of anything or received any new information at any stage of the pregnancy.

Note: If Holly had indicated to Ruth that she had a family history of MCADD, then she would have been referred to a paediatric specialist metabolic team. Additionally, if her other child, Jenny, had previously been diagnosed with MCADD, then this referral would also have been made.

Antenatal care

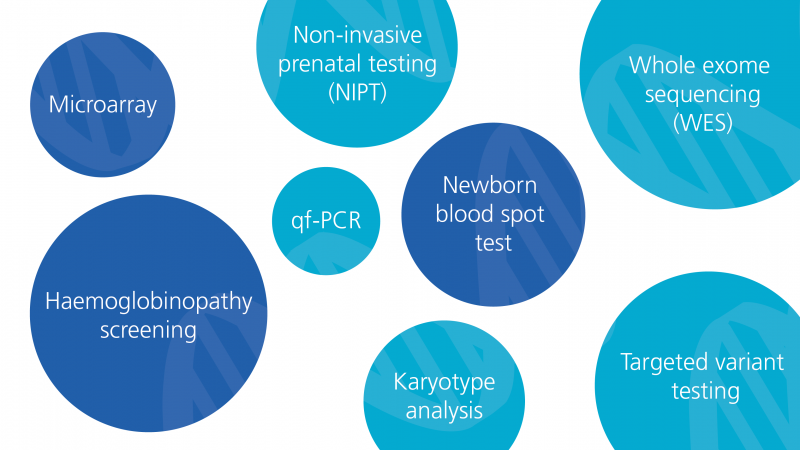

At 28 weeks, Ruth visited Holly at home to carry out an antenatal assessment and to take blood to check for anaemia and antibody levels. Before leaving, Ruth gave Holly a few booklets which described specific checks that would be carried out on her baby after the birth. One of the booklets referred to the ‘newborn blood spot screening programme’, a test that Holly remembered from her first pregnancy.

Holly told Ruth that her first child received a normal result after the blood spot test, which she described as painful and difficult to watch. Ruth empathised with her and made the benefits of the test clear. Ruth told Holly that, each year, a small number of babies get a positive result from the test, and in these cases, early diagnosis and prompt treatment can help to avoid severe developmental delay or other serious health problems. She mentioned that, sometimes, a special diet would be all that was needed to save the baby’s life. Holly took the booklet.

The birth

Jack was delivered at 39 weeks on the midwifery-led unit. Pete, Holly’s partner, was there for the birth. The birth went smoothly with no notable complications or problems. A few hours later, both Holly and Jack were perfectly healthy with breastfeeding going well, and so Ruth discharged them.

Neonatal care: the primary visit

Ruth visited Holly the next day for the primary visit: a neonatal check including the opportunity for Jack to have the blood spot test. Ruth informed Holly and Pete about the importance of the test, emphasising that a positive result, although rare, was a possibility, and finding out early could help to provide effective and potentially life-saving treatment for Jack. She also spoke about the limitations of the test, and told the parents that screening is not perfect, and a baby who is negative could go on to have a condition.

After listening to Ruth and remembering the booklet Holly had been given during her antenatal assessment, the family agreed to go ahead and get Jack tested that day. Ruth then obtained blood from Jack’s heel for the test. She informed the couple that after Jack’s sample had been screened, all remaining residual blood spots would be kept by the laboratory for research studies. Ruth recorded the details of the neonatal examination, consent consultation, procedure and discussion in Jack’s neonatal notes.

Before leaving, Ruth told Holly and Pete that she would contact them if there were any problems. Otherwise, the couple would be notified in six to eight weeks by letter or from a healthcare professional.

Neonatal care: diagnosis

Two days later, Ruth received a phone call from the metabolic screening laboratory who informed her that Jack had tested positive for a rare and life-threatening metabolic disorder called medium-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiency (MCADD). Ruth called Holly and Pete immediately to tell them that Jack had tested positive for a condition, and that she needed to see them to explain what the laboratory found.

Ruth met Holly and Pete to explain the condition, what causes it and how it was detected by the blood spot test in a clear and uncomplicated way. She made sure to answer any questions and took a note to find out anything she couldn’t answer.

Ruth asked how Jack had been since she last saw him. The family agreed that he wasn’t feeding well and was drowsy. Ruth recognised these as red flags and contacted the paediatric metabolic team immediately to arrange a consultation for Jack.

Note: Metabolic crises can escalate very quickly in people with MCADD, especially if a person develops a high temperature, vomiting or diarrhoea because the body requires more energy to combat the symptoms.

In the meantime, Ruth advised Holly to feed Jack every couple of hours and observe him for excessive sleeping and rapid breathing. Ruth gave the couple a leaflet to read with more information about MCADD.

Neonatal care: genetic basis and future pregnancies

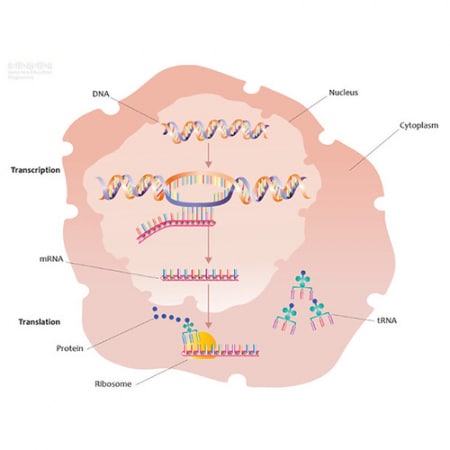

Pete asked why Jack was affected by MCADD but not the rest of the family. Ruth explained the autosomal recessive pattern of inheritance, drawing a simple diagram while talking through it. She explained that everyone has a pair of genes that make the medium chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase enzyme, and that neither of Jack’s pair of genes worked correctly because he inherited one non-working gene from Holly and another non-working gene from Pete.

She went on to explain that Holly and Pete are both carriers, each with one healthy copy of the gene, and this is why they don’t have MCADD themselves. She explained that when both parents are carriers, there is a 1-in-4 chance of having a child affected by MCADD, like Jack; a 1-in-4 chance of having an unaffected child, like Jenny; and a 2-in-4 chance of having a child who is a carrier.

Ruth also mentioned that any future pregnancies would be managed differently now that there is a known family history of MCADD, with immediate referral to the paediatric specialist metabolic team.

–

More information about MCADD is available on the NHS website. For help and support with planning and managing pregnancies with a chance of being affected with MCADD, it is recommend that you access your local guidance.